Body

Curated by Joy Pepe

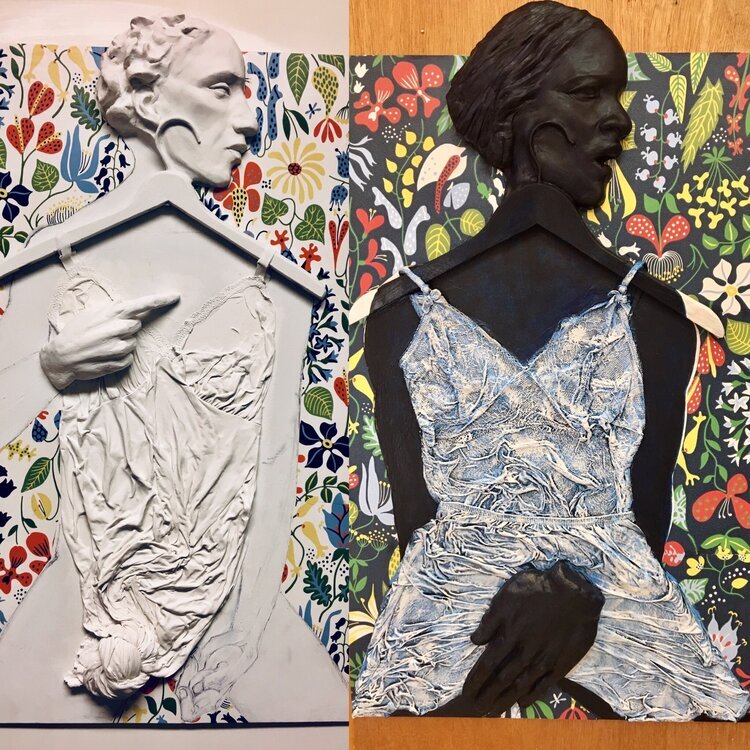

Beginning with three works of the female torso, Bleeding by Ingrid Barthelemy, Aušra by Molly Dee, and Winter Goddess by Lee Walther, we are challenged by the relations between natural sexual associations and the erogenous zones of the breasts and the strength of the upright unseen skeleton beneath the covering of soft flesh. Barthelemy reminds us of both the menstruation process as the red paint glides down the painting on either edge and the abuse of violence the torso can suffer from prejudices and control. Aušra, by Molly Dee, can be interpreted as the Lithuanian pagan goddess of the dawn, the morning star, daughter of the God. The truncated torso, without head, arms, or lower legs, suggests the literal fragmentation of surviving ancient sculpture, and the bright red, pink, and purple colors of the arising aura of the dawn sky that the goddess ushers in. The torso’s lyrical sway dovetails with the joyousness of a new day. At the same time, the sliced limbs and head imply the violence that can be done to the female form through the concentrated patriarchal gaze onto the sexual allure of the central body. A seasonal theme of the female torso as a Winter Goddess can also be analogized with the woman and nature theme discussed in the next section. In Winter Goddess, Lee Walther works with design that floats on the skin of the torso, yet also seems to be submerged just below its skin. Bursting florals and fruit shapes, intricate lace, and geometric lines suggest a sewing pattern draped over a mannequin. The design becomes a fashion statement of feminine possession of natural shapes and reasoned craft. Susan Clinard’s Closet Stories #1 and #2 carry on the connection of women and fashion with duplicates of seated or crouching women, cut at mid-thigh and head in strict profile, as they spill out towards us. Against bright, zippy floral patterns, recalling the female associations with nature and decoration, the white bas-relief figure and accessories on the left depicts a black hanger from which a scrunched up slip hangs, as she holds one hand near her genitals while another hand, large and masculine in comparison, covers her left breast and points towards the black figure who wears a white slip as her arms pull behind her back, a black hanger floats against her face. Another oversized hand covers her genital region. In both, the hangers’ top appears weaponized as it hooks into the side of the right cheek. Lingerie, fashion, flowers, and bodies signal the feminine, while profiles, skin colors, and enlarged hands connote issues of race and dominance.

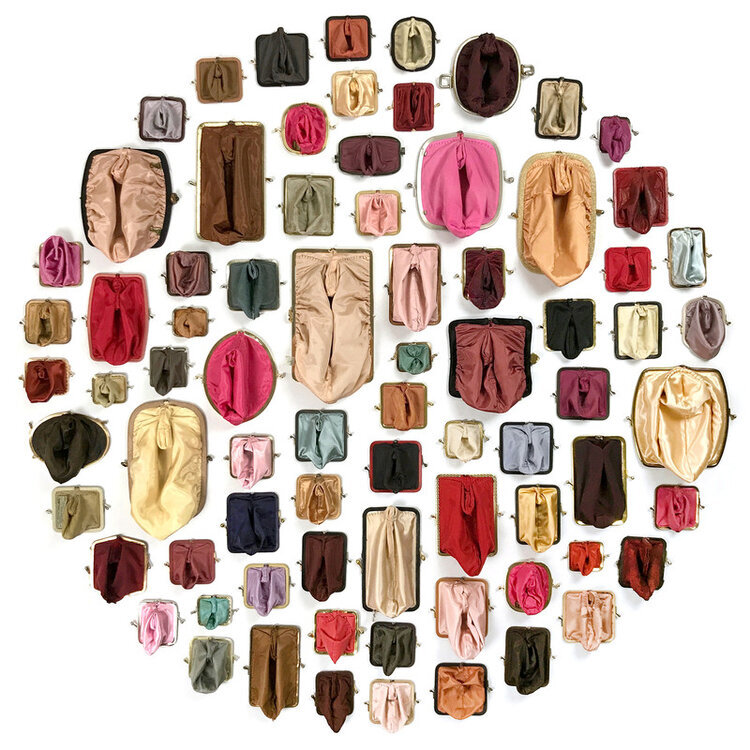

An expressively rendered female body holding a walking stick trudges towards us in Laura Shabott’s Woman with Walking Stick. The red paint aggressively becomes essentialized as menstrual blood, protective womb, or vaginal enclosure. She stares out with barely drawn features, and the walking stick can even remind us of a wind instrument, as in Matisse’s Music of the early twentieth century. She resembles an earth goddess or totem and can easily fit in the MAGIC section as well. But that straight walking stick moves us to Marsha Borden’s The Fire Down Below, where a red phallus shape inserts itself into a sheer, white lingerie top on a hanger. The fire is almost literal in the engorged shape below, but could suggest the sexual desire of women too, although they are less encouraged to express direct sexual desires with frankness and want. Both violent and erotic, Borden’s installation is provocative and off putting at the same time. The beauty of female anatomy and sexuality becomes literal in Suzanna Scott’s Coin Cunts, a circular arrangement of the silky insides of coin purses shaped as vaginas. The allure of the female sexual organ resides in the soft, smooth fabric and varied vaginal shapes, while the commerce of “sex sells” is literalized with the purses and the “shop ‘till you drop” stereotype of women, so associated with Barbara Kruger’s declamatory photograph of the early 1980s, is conjoined. Now that stereotype is shattered in the sexualized purses that, represent women’s economic independence and decision making power within Western capitalism. Megan Shaughnessy also focuses on the specifics of the female body, with a close cropped photograph of a lactating breast. The viewer has the sight that a baby has as white milk droplets, squeezed out by the mother’s fingers, leak onto the extended dark pink nipple, against ‘milky’ white skin. While within the iconography of the Lactating Madonna, Shaughnessy’s image suggests the caring role of the nursing mother, but also some of the sacrifice of self in that role, and the physical discomfort of the nurturing act.

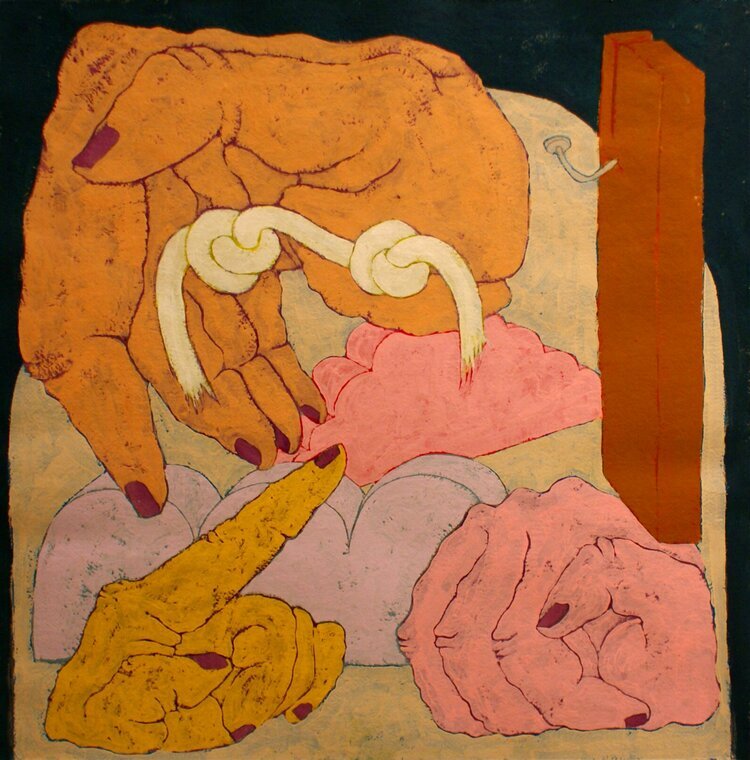

Austin Furtak-Cole’s quirky painting Where to Look, encapsulates his artistic debt to Philip Guston’s colorful and comic-like forms, although Guston’s work was often entirely autobiographical and/or political. But in Furtak-Cole’s work we are confronted by animated “amputated” body parts, here gnarly hands with disturbingly sharp red-painted fingernails. The hands cannot be attributed to any specific sex, but they point to a wooden post with a nail, or hold a small knotted rope, or curl into a loose fist. Unspecified organic mounds serve as landscape. Even with the bright comic-book palette and energetic line, the scene threatens a hanging, much as accused witches suffered within the confines of patriarchal and puritanical societies, and the potential for violence suffuses the scene. This uneasiness also pervades the presence and absence of the body creepily suggested in Annie Sailer’s installation of hanging jeans in Blue Jean Project: Magic 2. The entire work, just by its title, can be categorized within the MAGIC section, however, it is the lingering shape of the absent body in the drooping denim that suggests the former presence of that body and the viewer speculates as to what happened to those that inhabited these pants. Did they simply disrobe, are they missing, did they die, were there incantations performed to make them disappear? A creepy uncertainty exudes from the jeans, yet they also fascinate and compel the viewer to speculate on their sturdy presence and the fragility of the absent life which wore them.

— Joy Pepe, curator